Basics for consent and communication

Last updated: Aug 2025

Disclaimer: use at your own risk; no warranty of any kind. This page is just an add-on for preparing some of the theory parts we teach. If you spot any errors or have other tips for improvement, please let us know. Thank you!

Welcome aboard!

We are happy to support you on your journey in the world of rope. We have put together some important information for a smooth start and would be glad if you could take a quick look and read through anything you are not yet familiar with.

This page is updated from time to time, so it might be worth giving it a re-visit. If you are taking part in our classes, we will give you a hint about this anyway.

Tying means playing with physical restriction. In this context, it is crucial to practice excellent spoken consent.

Consent, to put it very simple, is giving or receiving the allowance for an action that would otherwise be morally wrong.

In order to establish good consent for rope bondage, we need some structure and tools:

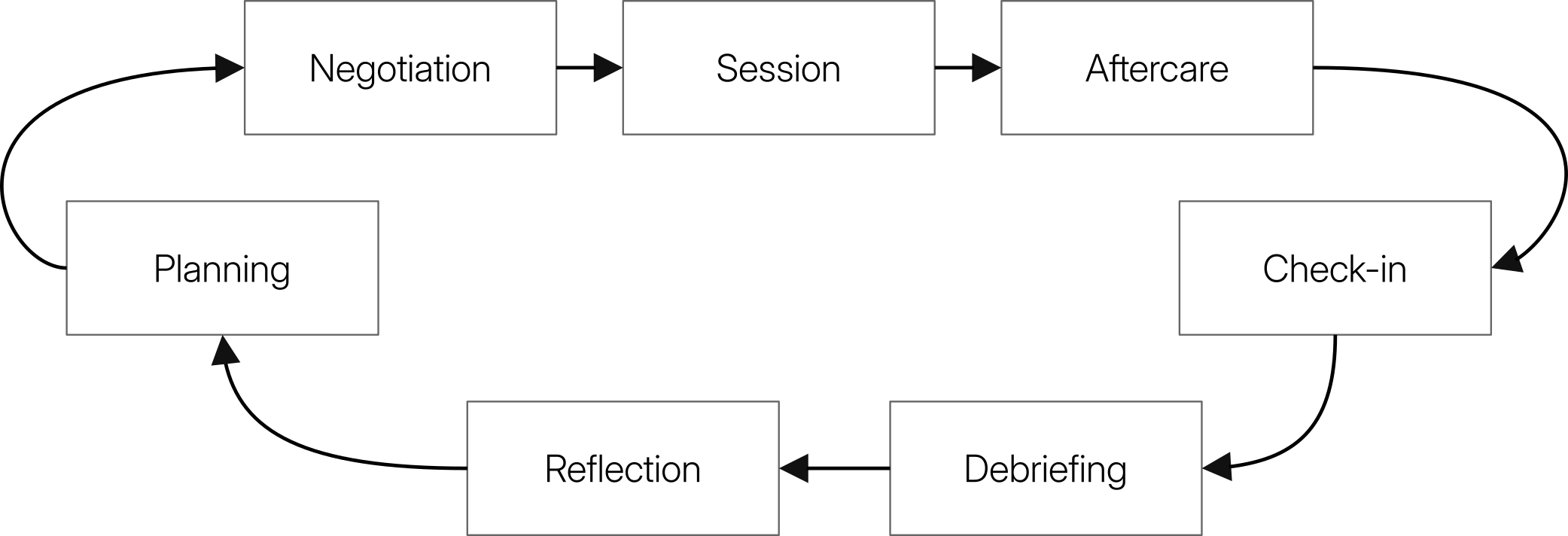

Sequence of a rope/play session

Before every rope session, there should be a negotiation. This should be very detailed before the first sessions together. As you get to know each other better over time, it can of course become shorter.

After a shared session, everyone involved is responsible for giving each other aftercare so that they can get back down to earth and, if necessary, back to an equal footing. The needs of each person differ widely. Some people like a lot of closeness (e.g. cuddling) to wind down, others prefer to be on their own. It generally makes sense to have a blanket, water or tea, and maybe a snack (muesli bar/etc.) ready.

A mutual check-in is often arranged, meaning a phone call or messaging the next day or a few days after the session. Often the emotions from a session continue to develop and can then be addressed again and mutual care can be offered.

A debriefing can take place immediately or (often more effective) at some time after the session. Perceptions and experiences can be reviewed here. What was great, what was perhaps rather irritating, unnecessary or unsuccessful? It is useful and important to deal openly with criticism and mistakes.

The results can be used as personal feedback and/or as a way of getting to know each other, and can be part of the next planning.

What should be discussed before a session?

A negotiation should fit the specific situation and take all relevant circumstances into account. Here are some useful inspirations:

Intention, knowledge, experience

- What is the aim of the session?

- Do the intentions of all participants match?

- Do they have the appropriate knowledge and previous experience?

Communication

- Do we use clear language? Or do we use a safeword or code, for example the traffic light system or the 0-10 scale? In the latter two variants, what does which signal mean?

- How can I recognize that you like something?

- How do I recognize when something is too much for you?

- How good do you feel today at saying stop or no and communicating boundaries when you don’t want something (anymore) or when something is too much for you?

- Do you sometimes freeze or become non-verbal when you are in pain, overstimulated or overwhelmed?

Mood and energy levels

- Enough sleep?

- Eaten and hydrated enough?

- How high is stress and tension today?

- Have you consumed alcohol or drugs?

- If applicable, have you taken medication as usual? Emergency medication, if applicable, in reach?

Physical limitations

- Do you have any physical limitations, pre-existing conditions or injuries? And what do they mean for our session, or our contact in general?

Wishes, needs and limits

- What types of play do you want? Which do you not want today?

- Where and how do you want to be touched, and where not?

- On which parts of your body is rope ok, on which not?

- Is there anything that you’re still concerned or worried about?

Informed consent, safety and aftermath

- Have the risks (marks, injuries, …) of all planned practices been discussed and can everyone estimate them?

- When will there be a debriefing and, if applicable, a check-in?

- What aftercare is likely to be required?

- Can it be ensured that everyone involved will get home safely afterwards (traffic safety)?

When is consent established?

Opt-out consent

In everyday life, we are often used to actively saying “no” or “stop” to end something we don’t want. This approach, known as “opt-out” consent, relies on our ability to intervene. However, it comes with challenges: something unwanted must have already occurred for us to stop it. Social pressures, emotional states, or stress may prevent us from reacting promptly or at all. Knowing that we are responsible for stopping a situation can also make it harder to relax and fully engage.

Ongoing consent

Another approach is to establish consent step by step during interactions, a practice called “ongoing consent”. This allows for adjustments in the moment, aligning with the evolving dynamics of the situation. However, it has its own challenges: we might make decisions differently in the flow of the interaction than we would with a clear mind, and frequent questioning can disrupt the connection and prevent a natural flow from developing.

Opt-in consent

To create a stronger foundation, discussing as much as possible beforehand — known as “opt-in” consent — can be very effective. While this may feel awkward initially, with practice, it can become a meaningful and connecting ritual. Reflecting on and communicating our needs clearly helps build a deeper understanding with ourselves and our partners. A defined framework established before the interaction also creates a sense of security, allowing us to engage more freely in the experience.

Of course, not everything can be addressed in advance. However, this should not be an excuse to avoid reflecting on and communicating our needs. “Ongoing consent” and an “opt-out”, the option to say “no” at any point, remain complementary strategies that are always available.

What is good consent?

There is an acronym that can help you remember the key ingredients for good consent: “FRIES” which stands for Freely, Reversible, Informed, Engaged, and Specific.

| Keyword… | …stands for: |

|---|---|

| Freely | Consent must be established without pressure, coercion or manipulation. All participants can decide freely, without fear of consequences. |

| Reversible | Consent can be stopped at any time, no matter how far something has already advanced. |

| Informed | Everyone involved must have the necessary information and capabilities to make a decision. |

| Engaged | Consent is given out of personal joy and persuasion. |

| Specific | Consent only applies to what has been clearly discussed. A “yes” to one thing does not automatically mean a “yes” to everything else. To avoid misunderstandings, intentions should be formulated as specifically as possible. |

Communication during a session

Shared responsibilities

Effective communication is a shared responsibility between both partners in a rope session. Riggers should be transparent about their skill level, needs, boundaries, and insecurities. It’s important to keep the model informed about what is happening throughout the session unless otherwise agreed upon.

Models, in turn, should communicate their own skill level, needs, boundaries, and insecurities. During the session, it is crucial to express how they feel both emotionally and physically. Any unpleasant pain, signs of injury, or nerve function impairment must be reported immediately to the rigger.

Effective tools for staying connected

To ensure clarity, you can use a scale from 0 to 10 during the session: 0 indicates no discomfort, while 10 represents unbearable pain. Before starting, discuss the model’s maximum tolerable level for the day and check in regularly to ensure their experience remains within this range. This provides a clear and simple framework for communication in stressful situations.